a conversation with common culture

David Evans: Why did you choose to call yourselves Common Culture?

Common Culture: Common Culture emerged out of conversations between David Campbell and Paul Rooney and developed into the collaborative project that now includes Campbell, Mark Durden and Ian Brown. It was originally conceived as a means of making art in response to the chauvinistic promotion of ‘Young British Art’ by prominent sections of the art establishment. As artists based in the North of England we were intrigued both by the claims of radicalism made by the cultural administrators in London for this new art and the notion of “Britishness’ it proposed. As a response, Common Culture began to make art exploring notions of Britishness, class identity and commodity culture from the perspective of our own social and geographic situation. The name Common Culture was prompted by reading Tom Crow’s Modern Art in the Common Culture (1) and reflected our wide-ranging interest in popular forms of culture. Since we are living in Britain our cultural references reflect specific local experiences associated with this country that are nonetheless framed and determined by global forces.

DE: Why the interest in fast food?

CC: We were only interested in illuminated fast food menus to the extent that they provided us with ready-made and familiar forms of commercial signage that could be adapted to reflect our interest in issues of taste, consumption and cultural identity. Our motivation was the opportunity to pit different forms of cultural consumption against each other, creating an awkward and self-conscious reception of the work for the viewer. We saw the light box form of the menus having corrupting allusions to Minimalism, the work of Donald Judd and Dan Flavin especially. We first exhibited this work in New York at the time of global interest in Young British Artists. The Menu work was about staining and soiling the pure forms of American High or Late Modernism with a vernacular trace of common transaction. And the whole fast food cuisine listed was in some ways an affront to the more refined tastes of the wine-sipping gallery visitor.

Common Culture, Bouncers, Portraits, 2005

DE: Recently you have been working with bouncers. So has Melanie Manchot, making videos of club bouncers on Ibiza who are asked to strip for the camera and in the process become uncharacteristically vulnerable. How does your project differ from Manchot’s Security?

CC: There is no relation for us. Our work with bouncers originated in questions to do with the commodification of labour power and the extraordinary power of the look these workers have. We were interested in using this within the context of the gallery, positioning this kind of looking in relation to that of the art audience. The work has different forms, performances, videos and a series of still photographs. Throughout this work and others, Local Comics, Mobile Disco and Tribute Singer, we have contracted people to work for us. In his respect, our practice has closer affinities with Santiago Sierra, an artist who was very important to our current book and show, Variable Capital. Sierra, like us, is interested in disrupting the exchange between viewer and artwork. Only his work is much more blunt and brutal in its exposé of what money can make people do. His art confronts us with global economic inequities. Sierra’s target and context is the international art market. Our work with people representative of familiar aspects of British culture is much more specific and local.

Common Culture, Bouncers, Performance Installation, 2005

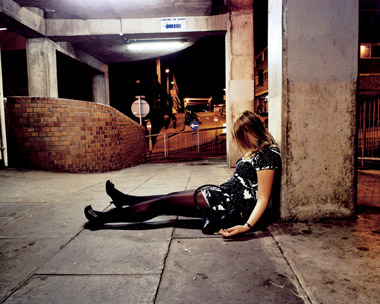

DE: A series of photographs from 2007 is called Binge dealing with the drinking sprees by young men and women that are now an established component of British urban culture. Are you endorsing William Blake’s famous suggestion that “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom”?

CC: No. It is a response to excess within British culture. In counterpoint to the disciplined and physically present bodies of the Bouncers, Binge focuses on states of satiation and abandonment, of collapsed bodies in the urban night scene. We do not celebrate excess but simply draw attention to the spectacle of people who have over-consumed. The Binge photographs and our earlier Menu work represent related stages in a dialectic of consumption. The Menus reference the signage used to incite consumption, while the Binge photographs chart its aftermath.

Common Culture, Binge, 2007

DE: You have just curated a show at the Bluecoat, Liverpool, called Variable Capital (2). Could you explain the title and say something about the thinking that informed this very ambitious exhibition?

CC: The title borrows a term used by Karl Marx to describe the proportion of capital invested in wages in the purchase of labour power. According to Marx it was this proportion of capital that produced a new, surplus value in the course of the labour process, over and above that paid to the worker as wages. Marx identifies this investment as the only one that creates new value, because the worker is able to produce more than he needs in order to live. Variable Capital creates the capitalist’s profit and is also the site of exploitation. Our show and book looks at art’s critical engagement with consumerism from Andy Warhol to the present. And looks at it within a global context— from Louise Lawler’s swanky photographs showing details of artworks for sale in the auction room to the video showing the repair of broken domestic appliances staged in a gallery in Caracas, by the Venezuelan artist, Alexander Gerdel. Art is of course the ultimate commodity and in many ways Lawler is key to the show in drawing attention to this, but there is also a focus on the role of workers and their deployment and exploitation as variable capital.

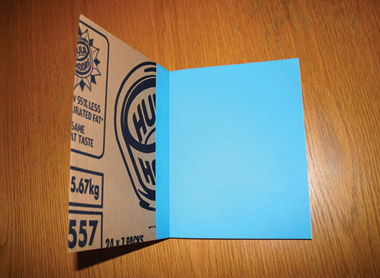

DE: You have created a tie-in book also called Variable Capital. It is published by Liverpool University Press, although it does not feel like a conventional academic publication. It’s a large, sumptuous, full-colour production, wrapped in a cover of re-cycled cardboard. Most obviously, you are alluding to the packaging that ensures that hi-fis, home cinemas, flat panel tvs and the like arrive in our living rooms undamaged, but I also noticed references to cardboard throughout your book. For example, an important section called ‘Exploitation’ considers the work of Santiago Sierra, especially the major piece Workers Who Cannot be Paid, Remunerated to Remain Inside Cardboard Boxes (1999). Could you say something about the thinking that informed the design of the book?

CC: The design of the book came about through a close relationship with an excellent design team in Liverpool, Lawn Creative. We wanted a look that signaled the book’s involvement with the traffic of commodities. The discussion with Lawn Creative centred on how to come up with a design for the book that would register its own status as a commodity, albeit one containing a critique of consumerism. Stephen Heaton, the designer at Lawn, proposed foregrounding the grubby reality of commodity transaction through the use of reclaimed cardboard packaging lifted from supermarket skips. As this material already carried the signage of its original life as commodity packaging and the utilitarian trace of its circulation and consumption, it was the perfect material with which to introduce the Variable Capital project. As a result of using the ‘found’ cardboard for the cover, each book is slightly different, bearing the signage, the brands and logos, for the products it once contained. To this extent each example is unique, a fact we further emphasized by giving each copy its own edition number.

The interior of the book is deliberately lavish and we wanted this contrast between the packaging and the product inside, beautiful colour images and a text that is quite detailed and academic but is presented in an enticing way. There was also a ‘Trojan Horse’ quality offered by the cardboard cover; a familiar material masking something potentially disruptive. Cardboard clearly signifies its status as a transient and disposable material, it is used in relation to materials and products deemed to be of greater value and status, it is always on the brink of being surplus to requirement and discarded. In this sense, its exploitation and abandonment is akin the capitalist’s treatment of human labour power, a central theme of the Variable Capital exhibition and book, so it seemed like an appropriate choice. You are correct in identifying a point of connection with Santiago Sierra’s Workers Who Cannot be Paid, Remunerated to Remain Inside Cardboard Boxes (1999). For Sierra the cardboard boxes serve to both cite the abstract geometric forms of Minimalism and commodity packaging. Cardboard as low and cheap material also was important as a contrast to the shiny seductive allure of the fetishized commodity and taps into what we refer to as work concerned with a thrift environment, the photographs of thrift stores by Brian Ulrich and the work of the British artist, Richard Hughes, who produced a specific piece for the exhibition that consisted of a meticulous fabrication of the cardboard packaging someone had been using as bedding in a street doorway.

Common Culture, Variable Capital, 2008

DE: The book has 26 sections, each given a curt title, usually of one word. The order isn’t alphabetical, yet the impression is of a dictionary of contemporary capitalist culture. Can your project be understood as a visually-led version of Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (1976) by Raymond Williams?

CC: The text can function like a dictionary, or as an ironic product range, but it is not the last or final word on the subject. It is important that the text was co-written and we wanted to get away from the form of the academic essay. The task was to produce a book that was seductive as well as critically engaging. The layout and the design mimics the presentational style of product promotion. The titles you refer to are there to entice, like the descriptions of dishes on a menu or goods in a product catalogue. The purpose of all this was to explore how artists have critically engaged with contemporary cultures of consumption and have done so knowingly, fully aware of their own status as producers of high-end commodities. The book was conceived as a partner to the exhibition of the same name at the Bluecoat, Liverpool. It was meant to provide a wider historical context for the artists we selected for the show, but the Bluecoat also brought its own context. Positioned as it is amidst a massive retail redevelopment of the city centre, the visitor to the gallery stepped immediately from Liverpool’s culture of capital with its bountiful new department stores into the Variable Capital exhibition. The friction with this context, 4 and the visitors’ experience as consumers, was just as important to us as mobilizing the historical context of commodity critical art.

DE: Jeff Wall is discussed in a section called ‘Bad Goods’, the title of one of his well known works from the mid-eighties that foregrounds rotting lettuces (and more cardboard) in a suburban wasteland. You cite Wall’s claim that his staged images continue a critique of documentary realism, but without the Brechtian or Godardian strategies of distanciation that had become ‘formulaic and institutionalized’ by the mid-1970s. Then in your ‘Conclusion’, you describe the work of Common Culture as a ‘Brechtian art [that] disrupts the familiar transactions underlying the experience of aspects of British popular culture.’ Do you see yourselves – as artists and curators – re-opening a debate about the use value of Brecht that many, like Wall, assumed to be closed some time ago?

CC: Yes, we do see our work as Brechtian in its disruptive and awkward relation to the viewer. We want a work that is unredemptive, that sets up a relationship with the viewer that is uncomfortable. Wall’s work sits too easily within the white cube art gallery, the potential brashness of the back-lit light box is countered by the art historical quotations his art make. Artists like Sierra are Brechtian and particularly uncompromising in their display of situations of exploitation within the gallery. Through the text, with its shopping list quality of organization and again in the exhibition, we were keen to develop the conditions where the reader or the viewer became aware of the possible relationship between the different work and the social situations to which they referred.

DE: Naomi Klein’s recent book The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism vividly articulates the suspicions of many – that the so-called War on Terror is above all a new, aggressive phase of capitalist development. Yet Variable Capital contains nothing directly related to this topic. Rather, its emphasis on American art of the eighties that dealt with the surface allure of consumer culture (Jeff Koons, say), contrasted with work from the same period that deliberately reveals the usually hidden labourer (Alfredo Jaar, perhaps) seems to imply that Klein and others are exaggerating the economic significance of the so-called War on Terror.

CC: Variable Capital is the beginning of a much bigger project that will take the form of another book. The idea of Disaster Capitalism is relevant and contemporary and will no doubt impact upon how we develop the project. Klein’s argument is not an exaggeration, but part of the wider global picture. But what was important in our conception of this project was to begin to track a recent art history that had not really been critically written. Our point of reference was the much more celebratory exhibition at Liverpool’s Tate, Shopping – A Century of Art and Consumer Culture. Our Menus were included in this show, but rather off stage, occupying the site of an un-rented shop on the dockside. Shopping included works by Koons, Prince, Steinbach, all artists we are interested in, but the show never really raised critical issues about their relation to consumerism. Our book discusses Neo Geo in contrast to the differing relations to a documentary photographic tradition that emerged in the 1980s, including work by Alfredo Jaar, Martin Parr, Paul Graham and Jeff Wall. Yet, with our interest in Brechtian strategies of disruption, such recourse to realist modes was never seen as the answer.